Introduction

2019 was a positive year for virtually all major asset classes globally and, overall, a year that widely exceeded expectations. At the end of 2018, the Fed was raising interest rates, recession fears were widespread due to the ongoing trade war between the world’s two largest economic superpowers, and all stock indices had fallen 15% or more within the fourth quarter. But in 2019, the Fed pivoted from its rate-hiking path and began to cut the Fed Funds rate while trade negotiations between the U.S. and China progressed. In response, global stocks ended 2019 significantly higher than they closed 2018, U.S. stocks ended the year near all-time highs, and U.S. interest rates fell in 2019, which boosted bond prices.

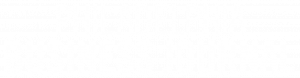

In fixed income, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index, which in 2018 had broken even, advanced more than 8.5% in 2019, lifted by falling interest rates. U.S. high yield bonds gained a solid 14.4%, thanks to both an economy that was stronger than had been feared at the end of 2018 and higher commodity prices. In stocks, the S&P 500 finished up 31.5% for the year, the MSCI ACWI Ex-USA gained 21.5% in 2019, and the MSCI EM advanced 18.42% (both in USD terms).

The United States and China remain the two engines of global growth. The U.S. likely grew 2.5% in 2019 and China 6.0%. The Euro area and Japan, on the other hand, are estimated to have grown less than 2%. Germany and Hong Kong both had negative quarters in 2019, and emerging market countries with high debt loads, such as Venezuela and South Africa, also suffered.

As we enter 2020, Sage’s view is that global growth will accelerate modestly from 2019 levels, driven by decreased trade tensions and the residual effect of the Federal Reserve’s rate cuts. The U.S. and China have verbally agreed to a partial trade deal (i.e., “Phase One” deal) that should boost business sentiment. Along with an exceptionally strong labor market, marked by low unemployment and positive real wage growth, the U.S. economy enters 2020 poised to continue its role as a leading engine of growth. Further, cyclical industries such as housing are likely to begin to see the positive effects of the Fed’s “mid-cycle adjustment” in Q1 2020. However, the U.S. may continue to drive global growth without a major change in the GDP rate, because the effect of the Fed’s monetary policy adjustment will largely fill the gap of the fading fiscal stimulus that helped to boost GDP above 3% in the first quarter of 2019.

Given this generally favorable macroeconomic backdrop, Sage expects equities to continue to move higher, albeit at a lower magnitude than 2019, and bonds to collect a coupon as interest rates trade within the current range. We think that cyclical industries will lead the way, spurred by lower interest rates and increased risk-taking by market participants. However, events such as the 2020 U.S. election, Brexit, and continued negotiations between the U.S. and China are likely to lead to higher volatility in asset prices than occurred in 2019.

2020 Outlook

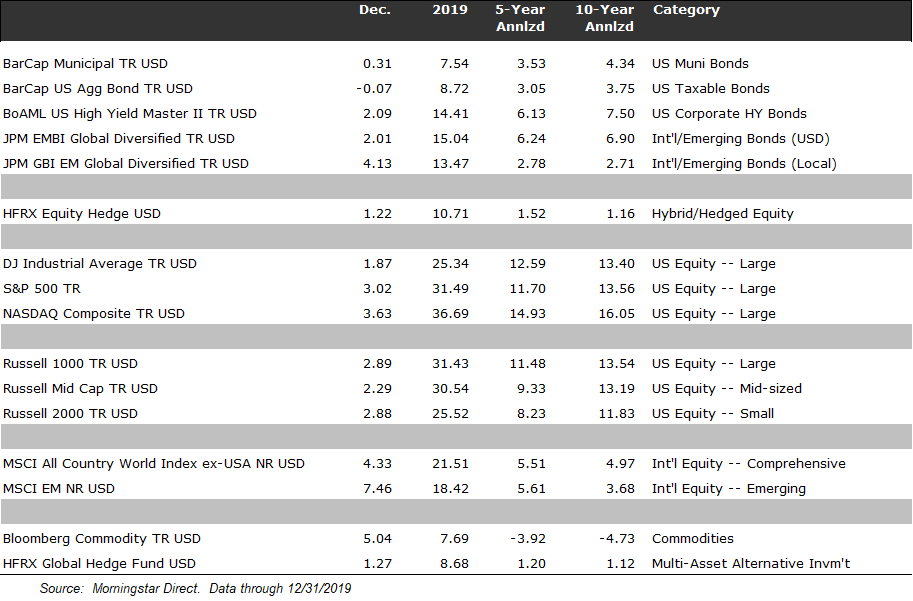

Headed into 2019, we expected a deceleration of growth both in the U.S. and abroad, which seems to have played out, as you can see from the nearby graph. The low starting point for equity markets, along with positive developments throughout the year, led the equity markets to very strong returns for the year.

Looking forward to 2020, we expect global GDP growth to turn upward based on three major themes: (1) trade tensions becoming less of a headwind than during the prior two years, (2) the global economy benefiting from the central bank easing that took place in 2019, and (3) the tight labor market in the U.S. continuing to drive consumer strength and spending.

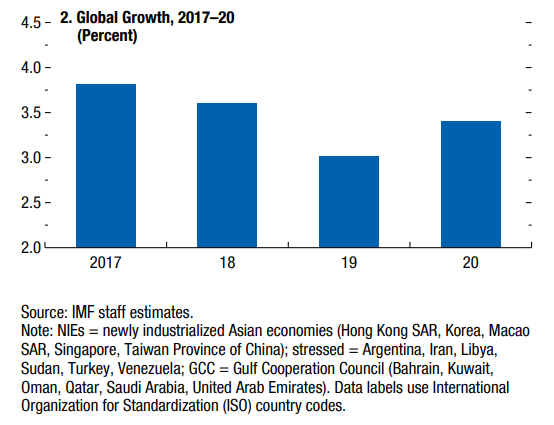

First, throughout 2019 trade negotiations between the U.S. and other large countries (namely China) were a constant headline source of uncertainty. However, progress was made throughout the year, and the U.S. administration began to prioritize stability over uncertainty as it headed into an election year. Threats of auto tariffs on European cars have subsided along with steel tariffs on Brazil. The partial “Phase One” deal between the U.S. and China was signed on January 15th, although further negotiations will continue throughout 2020 with the goal of reaching a comprehensive trade deal in the coming years. Given how much global trade has stagnated since the dispute between the U.S. and China started to flare in 2018, the anticipated improvement in relations could help to lift the rate of global trade in 2020.

Second, in 2019, the Federal Reserve and many other central banks were easing monetary policy. These changes take time to work their way through the economy. As a result, interest rate cuts made by the Fed in July may just be starting to boost economic activity now in Q1 2020. For example, interest rate declines may influence someone to buy a house at a lower rate, but it takes time for the purchase to take place. The same dynamic is true for businesses. When lower rates are available for debt, a business may decide to build a new factory or hire new workers but requires time to complete its plans.

Lastly, the U.S. consumer remains strong, and the labor market has recently been friendly to workers, as evidenced by low unemployment and higher wage gains. Euro-area growth offers less promise due to political instability, but growth overall remains positive, and inflation remains moderate. Growth for emerging markets, while unsteady in the first half of 2019, seems to have stabilized somewhat. China’s economy has been hit by the uncertainty of the U.S./ China trade tariffs, but its government is providing fiscal stimulus, and the transition of a manufacturing economy to a service economy is continuing apace.

There are risks to such a positive environment, however, which we outline on the left side of the table below. The most prominent risks in our view are (1) a re-escalation in trade tensions, (2) a U.S. election result that has an adverse outcome for markets, and (3) the manifestation of risks related to rising labor costs, including compressed profit margins, potentially restrictive monetary policy, and higher inflation.

On the flip side, a more positive market environment also is possible, outlined on the far-right column in the table below. A market environment that surprises to the upside would likely include (1) a comprehensive deal between the U.S. and China that boosts business sentiment, (2) technology advances that raise productivity significantly, and (3) decreased populist tensions in Europe and Asia.

The U.S. Economy

The U.S. economy grew at an above-trend 2.5% (est.) pace in 2019. The consumer has been the primary driver of growth, buoyed by a strong labor market. The U.S. economy is more services-based, as opposed to manufacturing, than many other countries around the world. Countries that rely more on service industries tend to be less cyclical and more dependent on consumer spending.

The current unemployment rate in the United States is 3.5%, which represents a 50-year low. Wage growth has strengthened, but it is not so strong that it is hampering corporate profit margins. Further, low oil prices should continue to increase consumption as 2020 gets underway.

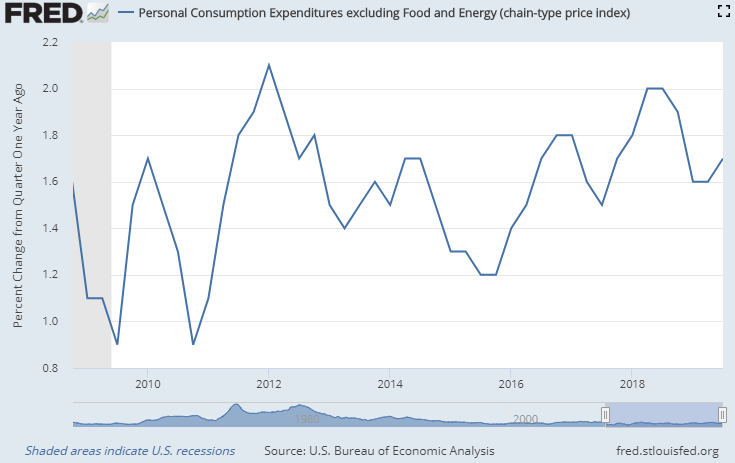

Wage growth has outpaced inflation by a significant margin, which means that the consumer has greater buying power. The most recent figures show that wages grew at approximately 3.1% year-over-year, while inflation has hovered around 1.5%, as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index. This implies that wages are growing at 1.6% on a real (i.e., after inflation) basis.

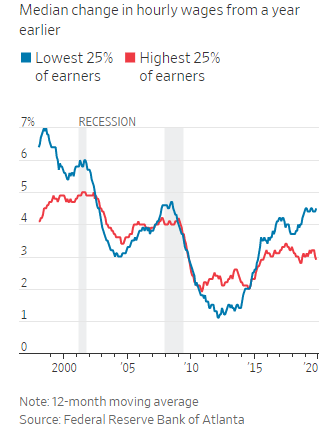

We believe that 2020 will see additional, if more limited, improvement in the labor market and consumer spending, as well as some improvement in business spending. Our base case is that unemployment will decline modestly or stay steady, and wage growth will modestly accelerate particularly for lower-income workers as the labor market remains tight. As is shown in the nearby chart, wage gains of the lowest 25% of earnings remain higher than that of the highest 25% of earners. This gap widened in 2019, and this is a trend that we expect to continue.

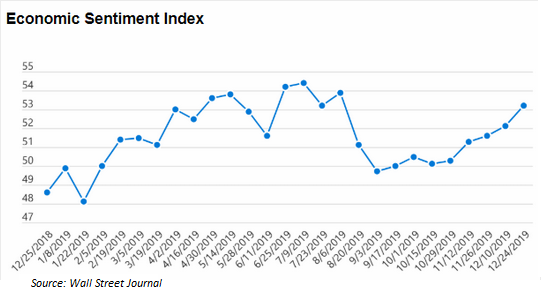

As shown below, economic sentiment improved throughout the back half of 2019, after being depressed at the beginning of the year.

Consumer spending represents more than two-thirds of the U.S. economy. Business investment is also a big portion of the economy and has been hampered by the trade war. As mentioned earlier, when there is major uncertainty in the marketplace such as a trade war between the world’s two economic superpowers, businesses may choose to delay expansion plans until more clarity is reached. Moreover, throughout 2019 many businesses were feeling the lingering effects of restrictive monetary policy implemented in 2018.

These two headwinds — trade war and restrictive monetary policy — appear now to be on the sideline, thus providing a more supportive environment for businesses.

There are risks to this outlook, however, including a re-escalation of trade tensions and the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Currently, the U.S. and China appear to agree that there will be no further escalations while talks of a comprehensive trade deal continue, but that could change. Further, campaigning for the U.S. presidential election will soon kick into high gear, and certain policy rhetoric could be damaging to economic and investor sentiment. Neither of these scenarios is our base case, but both are possible.

Overall, while not every sector is booming, the U.S. consumer is in good shape, jobs are plentiful, and businesses continue to benefit from increased consumer spending. We expect U.S. economic growth to moderate further from the likely approximate 2.5% rate in 2019 to a range of 1.50% to 2.50%.

U.S. Federal Reserve

U.S. monetary policy has been on a roller coaster throughout the past few years. During 2018 the Federal Reserve raised rates four times, once each quarter, and began to reduce its balance sheet through a process called quantitative tightening. As a result, financial conditions became significantly more constrained, and the Fed realized at the beginning of 2019 that the effect of tightening was greater than it had anticipated. No statement was more mistimed than Chairman Jerome Powell’s announcement in his press conference in December 2018 that the balance sheet runoff program was on “auto-pilot.” In January 2019, Chairman Powell reversed course and signaled clearly that the Federal Reserve was on hold with respect to rate hikes and that the balance sheet size was flexible. This policy pivot was perhaps the most important moment in 2019 in terms of restoring confidence that the Fed’s efforts to fight inflation would not induce a recession. In the second half of 2019, the Fed then reduced interest rates by 0.25 percentage points on three separate occasions (July, October, November), and in the fall, it began to expand its balance sheet again via repurchase agreements to aid with shortages in liquidity.

After the past two very active years in monetary policy, we currently expect the Federal Reserve to take no action in the way of interest rate changes. In Sage’s view, the bar is extremely high to raise rates due to a lack of inflationary pressures, and financial conditions have gotten so easy with growth remaining steady that it seems unlikely the Fed will cut.

In terms of inflation, there is very little evidence that inflationary pressures will drive up prices excessively in the near term. In fact, the Fed has signaled that it is likely to adopt a formal change in the way it targets inflation, namely, that it will follow average inflation targeting as opposed to the current policy, which is better described as targeting a 2% inflation every year regardless of previous inflation rates. Under the average inflation targeting scheme, the Fed would aim for 2% inflation on average over the multi-year business cycle, which in practice means that inflation must run a little higher than 2% during expansions to make up for an expected or actual shortfall of the inflation target during periodic downturns.

Since the beginning of the current economic cycle, for instance, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the core PCE price index, has stayed at or below its target of 2% in all but one reading, which occurred in 2012. A move to inflation averaging may mean that the Fed allows inflation to run at 2.5% (or higher) for an extended period. In practice, this policy implies it will take a much higher level of inflation, which we have not seen in more than a decade, for the Fed to implement aggressively restrictive monetary policy through higher interest rates.

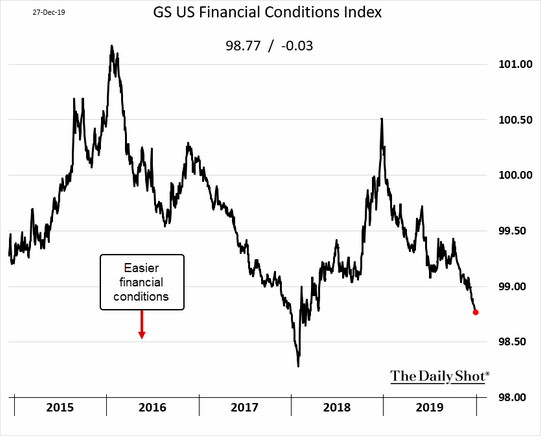

While we think it is possible the Fed will cut rates by 0.25% once in 2020, it seems more likely at this point that it will not need to cut rates at all. As shown below, according to the Goldman Sachs U.S. Financial Conditions Index, conditions for companies were the most restrictive at the beginning of 2019, but they are currently at one of the easiest levels in the past five years. The three major components of financial conditions are (i) interest rates, (ii) credit spreads, and (iii) equity prices. Currently, interest rates are near all-time lows, credit spreads are well below historical averages, and equity prices in the U.S. are at all-time highs. Unless something unforeseen changes the environment, such as a re-escalation of trade tensions, the Fed seems highly unlikely to change its rate policy in 2020 and likely will hold rates steady. The bar to raise rates is much higher than it is to cut rates one more time.

Global Central Banks

Due to the deceleration of growth in the global economy, 2019 was a year in which many central banks eased monetary policy, and we expect more of the same in 2020. Trade tensions were a drag on global economic growth, particularly in manufacturing, and many central banks cut rates to help boost economic activity. The European Central Bank (ECB) had projected that it would raise rates in 2019, which we doubted, and they were unable to follow through on their stated plan because of weakness in critical areas. For instance, Germany, whose economy depends heavily on manufacturing, had one quarter of negative GDP growth in Q2 and narrowly avoided a recession by posting 0.1% growth in Q3. The response by central banks to broader economic slowdown has been to reverse the course of quantitative tightening and planned rate increases and shift back to easing policy measures and lower rates.

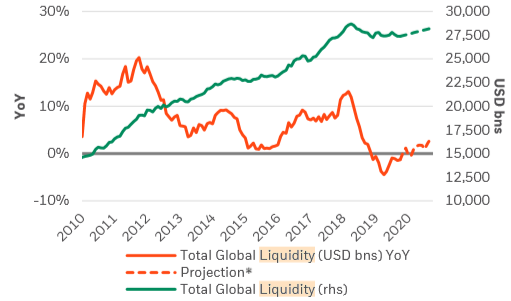

As we enter 2020, liquidity from central banks is again turning positive. Put simply, restrictive monetary policy shrinks the overall money supply, which decreases the possible demand for assets, including stocks and bonds. The rate of change of money supply is what matters. As shown below, the growth of the money supply should begin to accelerate in early 2020 (i.e., by decreasing at a slower rate). This policy pivot away from restrictive policies (i.e., raising rates and quantitative tightening) to looser monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and other global central banks is a very important theme and should be supportive for equities (Source: BlackRock).

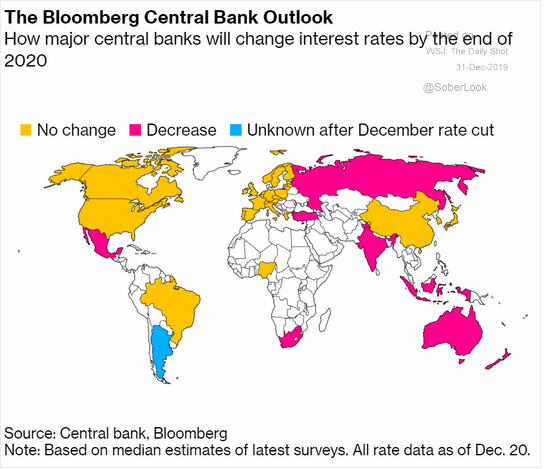

We expect this trend of easier monetary policy by central banks to continue throughout 2020. The map below shows which countries’ central banks are anticipated to cut rather than raise rates in the coming 12 months. As of now, no major central bank is expected to raise rates, and many are expected to cut to spur economic activity in their respective countries.

This move towards easier financial conditions should be a positive for markets, but there is a risk that the eventual benefits from additional monetary easing policies in Japan and Europe are not as great as they were previously. The risk is particularly pronounced in Europe, where the ECB cannot cut rates further and any easing would need to be via asset purchases. Said differently, many places including Europe could be reaching a point where fiscal stimulus is needed to achieve higher levels of growth and inflation. Europe’s structural issues remain due to the fragmented nature of the Euro Zone economic and monetary union, which poses a continuing challenge to policy-setting.

Fixed Income Outlook

In Sage’s view, accommodative monetary policy and continued steady growth from the economy will lead to a range-bound fixed income environment in both (1) interest rates and (2) credit.

Interest rates have fallen significantly in this economic cycle as a result of central bank bond purchases, along with expectations for lower inflation and slower growth. As shown in the chart below, the U.S. 10-year note yield fell precipitously throughout the first 8 months of 2019 but steadily rose throughout the final quarter. Not coincidentally, the turning point for U.S./China trade negotiations occurred in September, which lifted the sentiment of consumers and market participants.

Looking forward to 2020, in the context of a growing economy but accommodative central banks, Sage expects rates to continue to rise modestly, but demand for yield to keep rates lower than we have seen in recent years. Yields could creep higher, but we think they will remain range-bound throughout 2020.

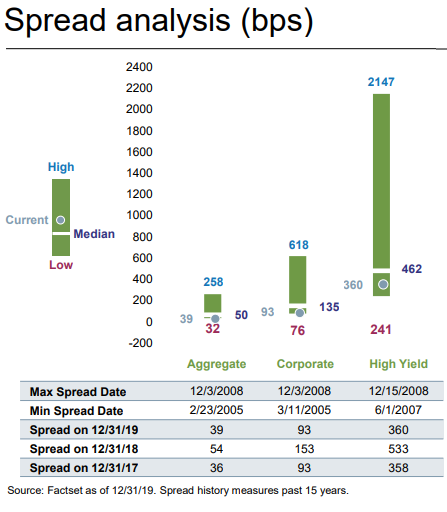

The other element of fixed income returns is known as bond “spreads,” which remain low on a historical basis both in investment grade and high yield. Bond spreads measure how much investors are being compensated to invest in risky debt versus government debt, and tighten (i.e., get lower) to reflect improving economic conditions. When spreads get lower, bond investors benefit. When spreads widen (i.e., get higher), bond investors see losses. Sage does not think that spreads can get much tighter, and this initial condition will create a lower total return environment for fixed income investors going forward.

Further, there are some risks in corporate credit, especially in specific pockets such as leveraged loans. Underwriting standards have continued to decline, which means that weaker companies can hold higher levels of debt and continue to access capital markets. Over time, some of these weaker companies will eventually go out of business, and investors may not be as protected as they had believed. These two reasons – tight corporate bond spreads and worsening credit underwriting – are why we continue to avoid an explicit high yield position in client portfolios.

Overall, we think that rates will rise modestly over the next year but largely trade within a tight range. Demand for yield will likely cap rates below what we saw earlier in the current economic cycle. From a spread perspective, we do not think that conditions can improve enough to lead to further spread compression. An environment of slightly higher rates and stable spreads will likely leave fixed income investors with a positive return in 2020, but lower than experienced in 2019.

Equity Outlook

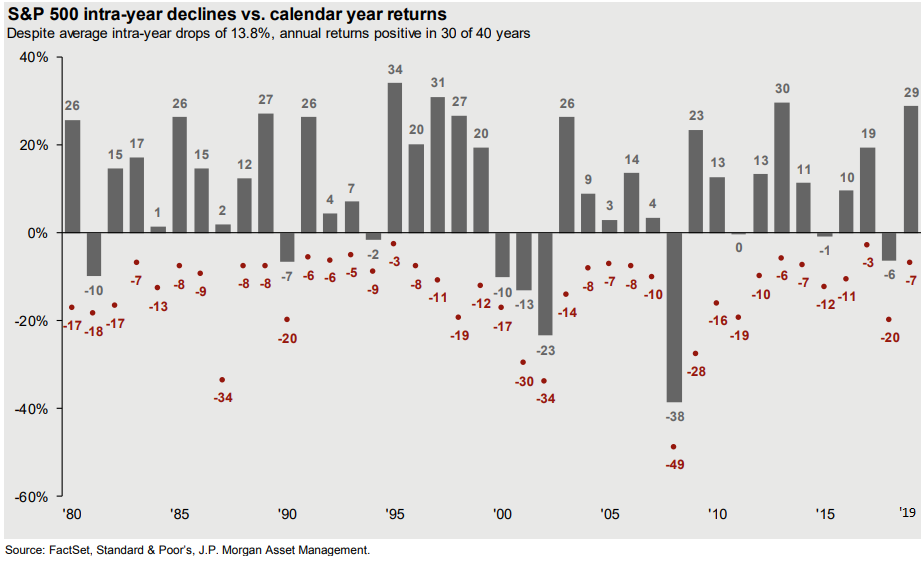

Following a volatile 2018, 2019 was characterized by a correction-free climb upwards. As shown in the chart below, the largest S&P 500 drop was only 7%, resembling the bull run of 2017. Thanks primarily to progress on the trade front and easier monetary policy, 2019 was a banner year for major stock indices. The S&P 500 returned more than 30%, and the global stock market, as measured by the MSCI ACWI, was up approximately 25%. Looking forward, we expect that the global economy will continue to grow this year and that equity returns will be moderate in 2020.

As we survey global conditions, we think that easing trade tensions, non-restrictive monetary policy, and an uptick in global economic growth will boost stocks, although the gains are likely to be lower than in 2019 partly because of full valuations. Companies that are focused on faster-growing emerging markets are likely to lead the way, while Europe may remain challenged due to structural issues such as demographics and fragmented politics, along with the fact that its central bank has very little room to boost growth through monetary policy.

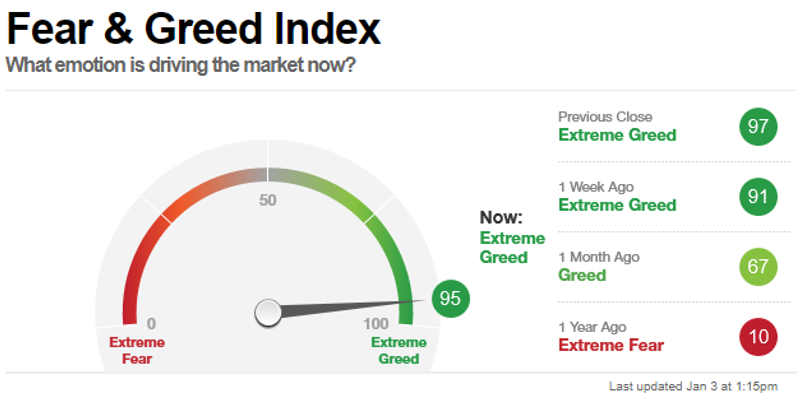

In last year’s Outlook, we noted that the “CNN Fear & Greed Index [had] calculated that [at the time] there is ‘extreme fear’ in the markets,” which was likely a counter-indicator that would lead to positive returns in 2019. On this front, we were correct. At the end of 2019, the CNN Fear & Greed Index was on the other end of the spectrum, registering as “extreme greed.” Although that reading is concerning on the surface, there are legitimate reasons, as we have explained above, to be optimistic heading into the new year, including easing trade tensions, a slight pick-up in global economic growth, and mostly stable Fed policy in the U.S. and responsive central banks abroad.

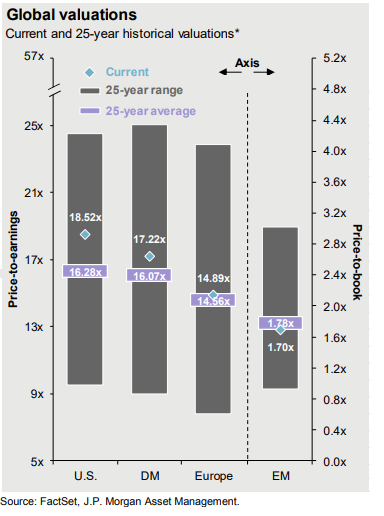

An examination of global equity valuations may help to explain the current CNN Fear & Greed Index reading for U.S. stocks. As you can see from the graph nearby, as of 12/31/2019, U.S. stocks (measured by the S&P 500) were trading at a next 12-month valuation level above the index’s average over the last 25 years. The same is true for developed market stock indices as a whole, with Europe in particular just peeking out above its average valuation level. EM stocks were essentially level with their 25-year average level.

Against the backdrop of a truce to U.S./China trade tensions, a more dovish policy pivot by major global central banks, continuing U.S. consumer spending sentiment and outlays, and China’s recent fiscal stimulus and loosening of financial conditions, EM equities might be among the more attractive opportunities within global equities; however, they remain right at their 25-year average.

Put differently, none of these equity indices or composites is significantly undervalued. After a year of strong returns as 2019 was for stocks, with valuations at these levels, it would not be unheard of for some bout of price volatility or a correction to occur, which is perhaps an implication of the CNN Fear & Greed Index. The point of that indicator is simply that U.S. equities are priced at levels that have typically seen future returns lower than those that pumped up the index to levels in the 90s (the current level is 95).

Overall, we think that equity markets have many tailwinds, including improving economic growth and a better trade environment. However, we take both of these factors — the greed/fear reading and the global valuation metrics — as signals to investors to have more modest expectations about returns for the next 12 months. These expectations might still be positive, as ours are, but there are reasons to keep them modest.

Portfolio Implications

Our outlook for 2020, as outlined above, influences our thinking about portfolio positioning in the following ways.

- Fixed Income:

-

- United States: In the U.S., bond yields will likely trade within a range but not suffer a sustained spike higher. However, because of the potential for a “watch-and-see” approach by the Fed and the potential for steady economic growth, we have a little less duration in our portfolios than we would generally expect to have over the long term.

- Foreign bonds: The persistence of low and some cases negative bond yields in developed market countries such as Japan and Europe makes EM bonds, with higher yields and a backdrop of likely increasing growth, more attractive to us on a relative basis.

- Equities:

-

- United States: Given our outlook for relatively steady growth and no recession, we anticipate maintaining our slight overweight to U.S. stocks with a bias toward large-caps.

- Foreign stocks: EM stocks may present a better return opportunity than developed market foreign stocks because of lessened but remaining uncertainty about Brexit and structural (demographic and political) challenges in Japan and Europe.

- Alternative Investments:

-

- In view of low current interest rates, tight spreads (from a fixed income perspective), and average or somewhat elevated stock valuations (from an equity perspective), we will be on the watch for opportunities to add diversifying strategies in 2020.

-

- Incorporating non-traditional assets and strategies into our current portfolios could allow for additional sources of potential return since we think that in the coming years portfolios may not need to rely as heavily on traditional stocks and bonds as they do now.

Concluding Thoughts

We expect global growth to rise modestly in 2020 from near 3% to near 3.5%, and this expansion may be led by emerging markets. A combination of easier monetary policy/financial conditions and stabilization in trade disputes should ensure that the U.S. avoids recession and continues to grow. While we think that a recession in the U.S. is unlikely, we do think that full equity valuations (at or above 25-year averages) and the possibility of idiosyncratic economic or geopolitical events (including the U.S. presidential election) could introduce the risk of corrections at times. Overall, we believe that the mid-cycle adjustment to lower interest rates by the Fed and more accommodative monetary policy by other global central banks, combined with strong employment and consumer spending in the U.S. and the promise of an end to escalation in trade policy, is likely to result in a continuation of economic expansion and conditions that support positive, if more moderate, returns in financial markets.

No one can predict how the markets will behave, or what political and world events will unfold. What we can do is be mindful of our clients’ long-term goals so that we can position their portfolios for a wide range of potential present-day economic outcomes. At the start of last year, many investors expressed worry about owning stocks and other more aggressive investments. We assured them that we hold these assets not because we know precisely that a given calendar year will produce good results, but because over a multi-year perspective stocks and other related investments are still likely to be the highest returning asset class despite a series of mostly unpredictable ups and downs along the way. We continue to hold them for the same reason and despite the possibility of an occasional hiccup. We continue to hold a mix of bonds and other diversifying investments for related reasons—not because of a guarantee that one of them will perform spectacularly in a given year, but because over time portfolios appropriately mixed with diversifying assets are more likely than not to help clients advance toward their financial goals.

The information and statistics contained in this report have been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable but cannot be guaranteed. Any projections, market outlooks or estimates in this letter are forward-looking statements and are based upon certain assumptions. Other events that were not taken into account may occur and may significantly affect the returns or performance of these investments. Any projections, outlooks or assumptions should not be construed to be indicative of the actual events which will occur. These projections, market outlooks or estimates are subject to change without notice. Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this newsletter will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. All indexes are unmanaged and you cannot invest directly in an index. Index returns do not include fees or expenses. Actual client portfolio returns may vary due to the timing of portfolio inception and/or client-imposed restrictions or guidelines. Actual client portfolio returns would be reduced by any applicable investment advisory fees and other expenses incurred in the management of an advisory account. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this newsletter serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from Sage Financial Group. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability above to his/her individual situation of any specific issue discussed, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. Sage Financial Group is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of the newsletter content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the Sage Financial Group’s current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available for review upon request.

Sage Financial Group has a long track record of citations and accolades. Rankings and/or recognition by unaffiliated rating services and/or publications should not be construed by a client or prospective client as a guarantee that s/he will experience a certain level of results if Sage is engaged, or continues to be engaged, to provide investment advisory services. Nor should it be construed as a current or past endorsement of Sage by any of its clients. Rankings published by magazines and others generally base their selections exclusively on information prepared and/or submitted by the recognized advisor. For more specific information about any of these rankings, please view Accolades page or contact us directly.

© 2020 Sage Financial Group. Reproduction without permission is not permitted.